diplo.news

Basketball, sauna and an aviator from Germany

By Gudrun Dometeit

If anyone knows how to ease tensions, it's Markku Reimaa. The Finn dedicated at least 18 years of his diplomatic life to collective security in Europe and saw how the gun-staring opponents of the Cold War, the Warsaw Pact states and NATO, gradually converged. Reimaa's voice is still proud to have accompanied the historic process from day one, starting with the preparation of the first Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE) in 1973 to the signing of the Final Act on August 1, 1975 in Helsinki and the last follow-up conference in 1990 in Paris, which officially declared the end of the Cold War. The East-West Conference, compared by some historians with the significance of the Congress of Vienna, not only reorganized post-war Europe, in which two political and economic systems rivaled each other. Above all, it was a great piece of diplomatic history, with all the finesse, with shuttle diplomacy and side agreements, which began with the recognition that military strength and cooperation are not opposites but two sides of the same security medal.

It was in July 1972 - Reimaa had just taken up his first post at the Finnish Mission in East Berlin - when he received surprising news from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Helsinki: he was invited to become part of the Finnish CSCE delegation as the eighth member. “It was a great honor,” he says. After all, the diplomat was just under 30 years old, a young attaché in the group of old hands. Neutral Finland had already offered to host a European security conference in 1969 — it saw an opportunity to promote itself and its neutrality policy, which was not met with enthusiasm everywhere in the divided continent.

“Helsinki is not a big city,” says Reimaa. “Back then, we were startled to ask ourselves: Do we even have enough hotel capacities and conference rooms?“ We did. Shortly before, the Finlandia Hall — the futuristic event building by the famous architect Alvar Aalto — and a new intercontinental hotel had been completed, as was the Dipoli Conference Center at the Technical University a few years earlier. In November 1972, around 350 embassy representatives from NATO-15 countries, seven Warsaw Pact states and 13 neutral countries were invited to a preparatory meeting there. “The Russians immediately said yes and even sent a Deputy Foreign Minister,” says Reimaa. “They wanted to adopt a declaration on the status quo after the Second World War as quickly as possible, in which the existing borders and a renunciation of violence were to be confirmed. They wanted to be ready by Christmas 1972. “Nothing came of it. Initially thought of by some as a nice but short chat over tea and cookies, the meeting turned into a serious event. The first working groups were set up from January 1973, and their aim should not be declaratory phrases but concrete suggestions. The Soviet Union under CPSU party leader Leonid Brezhnev agreed or at least not against, albeit gnashing his teeth.

If the Soviet Union had had its way, the declaration it wanted would have been made much earlier anyway. As early as the 1950s, it proposed a conference that would secure its own sphere of influence in the east, neutralize Germany and keep the USA and Canada out of Europe. In 1967, NATO was actually prepared to hold talks in principle - encouraged by the Belgian ambassador at the time, Pierre Harmel, to focus not only on military deterrence but also on cooperation in order to maintain peace. After the suppression of the Prague Spring by Warsaw Pact troops in 1968, the willingness to talk was over for the time being, but once the West had come to the conclusion that the act of violence was not directed against itself and the Soviet Union had also agreed to the participation of the USA and Canada, the course for a conference was set again. The Four-Power Agreement and the so-called Eastern Treaties, which Willy Brandt concluded with Moscow, Warsaw and East Berlin in order to approximate and normalize relations, also contributed to this. Incidentally, at the beginning of 1973, in response to criticism from the CDU/CSU opposition in the Bundestag, Brandt emphasized that the basis of his peace policy was partnership with the USA.

The personal factor: diplomats from East and West even spent their free time together

“We were a big social community,” Reimaa remembers the many meetings that took place after the Finnish kick-off in Geneva, where the participating diplomats and their families had moved. “No wonder, we worked together almost 24 hours a day, seven days a week.” For Eastern Europeans, dealing freely with one another was completely new, but many would have quickly come to appreciate it. “In our free time, we played basketball against the Soviet representatives, and then we went to the sauna. You got to know your personal characteristics, who was willing to make compromises or who was one of the doctrinaries and was a tough nut to crack.” With some, you could even discuss personal things, such as raising your own children. Reimaa discussed bilaterally behind closed doors with Soviet Ambassador Yuri Kashlyev in order to then jointly submit proposals to the big group. According to Kaschlyev later in his memoirs on the CSCE, Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko's aim was to conclude a treaty binding under international law and thus to have the results of the Second World War - the recognition of new borders and the division of Germany - confirmed multilaterally. The CSCE should be a kind of substitute for a peace treaty.

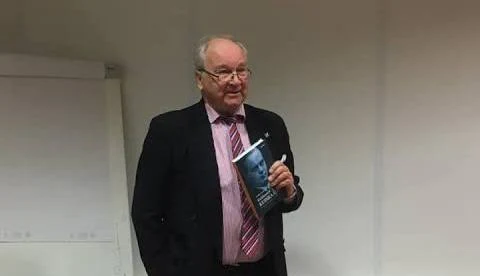

Because this goal was so important to the Soviet Union and Brezhnev in particular, they agreed to talk about the sensitive issue of human rights in addition to security and economic issues. Reimaa's task was to develop suggestions for human contacts, family reunification and exchange of information with Eastern Europe. And to keep records at the same time. But this was barely achievable in view of the tense work involved. Reimaa only fulfilled its chronicle duty in 2008 in a separate book (“Helsinki Catch”). The young Finn experienced the struggle for words and principles, how the participants talked in front of and behind the scenes, how important they took themselves or what tricks they used to work with. At the opening conference of foreign ministers in 1973, Germany's supreme diplomat Walter Scheel (FDP) behaved “like the representative of a superpower,” he remembers. Scheel was flown from eastern Helsinki to Finlandia Hall in a helicopter. At the closing reception on a hot summer evening, he served food and drinks in the elegant Hotel Haikko, which an Air Force transporter had specially brought from Germany. Reimaa also experienced how unenthusiastic US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger was initially about the multilateral format of the conference because he did not want to be talked into relations with Moscow and considered the parallel disarmament talks on reciprocal and balanced troop reductions to be more important. “And he wanted to prevent it from turning into a conference about a divided Germany. ”

Heads of state and government, a total of 550 delegation members, 3,000 assistants, advisors and security guards gathered in Helsinki for the final conference on August 1, 1975. 550 police and soldiers watched over the mammoth event. 1410 journalists were accredited. Helsinki residents saw an endless train of black limousines rolling towards Finlandia Hall, which was popularly known as “Kekkonen's Fish Trap.” Finnish President Urho Kekkonen was regarded as a puppet master and staunch sponsor of the conference. In the final declaration, the participants — including Helmut Schmidt and Erich Honecker, who always forced the Francophone alphabetical seating arrangement side by side — committed themselves to the inviolability of borders, to the peaceful settlement of disputes, to non-interference in the internal affairs of other states and to the protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms. They agreed on economic cooperation and confidence-building measures, such as the announcement of manoeuvres and communication channels in the event of a crisis.

The channels of communication remained open, especially in times of crisis

According to Reimaa, one of the last sentences was the wording that the agreements did not mean renouncing German reunification under peaceful circumstances. “That was revolutionary.” It met the national interest and overriding wishes of the Federal Republic of Germany and was one of the most controversial topics of the conference. The adoption of the Final Act based on these principles could also have failed. “In the summer of 1975, there was actually the last chance.” Also because the position of the ever more sickly Brezhnev in the Politburo of the CPSU began to crumble. A few months later, the Soviet Union began deploying SS20 medium-range missiles that could reach Western Europe and would have disconnected the Europeans from the US nuclear shield. A clear violation of efforts to relax — although NATO was also working on modernizing its medium-range nuclear missiles at the same time.

However, Reimaa, who accompanied all subsequent conferences, regards the CSCE as a success. “It provided a channel for dialogue in a time of international unrest and prevented crises from spiraling out of control.” And there were many of them: the division of Cyprus, the military coups in Greece and Portugal in 1974, the invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, martial law in Poland 1981, or the rapid successive deaths of the three Soviet Secretaries General Brezhnev, Yuri Andropov and Konstantin Chernyev Enko in the eighties. “But the biggest success of the CSCE was the peaceful disintegration of the Soviet Union,” the 82-year-old is convinced. “The CSCE then became a kind of umbrella for all states that were no longer part of the Soviet Union.” Many opposition figures in Eastern Europe relied on the Helsinki Principles. According to Reimaa, the Russian dissident lists only became really empty under Mikhail Gorbachev, beginning with the return of atomic physicist Andrei Sakharov from exile in Gorky in 1986. And yes, Finland's role may not have been as decisive in terms of content input, but everyone had praised their country's hosting role and tireless diplomatic efforts. “It was also a symbolic recognition of our neutrality policy. ”

Reimaa believes that the consensus principle, which was agreed upon right from the start, was decisive for the success of the CSCE process. Unanimity was not required, there was simply no no answer. “And consensus always meant compromise.” All participants, even the Soviet Union, would have renounced the ideologically pure line.

Would a new, similar conference be repeated in the current tense situation with a war between two European states, Ukraine and Russia, as well as an enormous rearmament? Like back then, at least as a prelude to a process of relaxation? After all, it was also clear to everyone in 1975 that the Helsinki conference would only be the beginning of the end of the Cold War. And what contribution could the successor organization OSCE, founded in 1995, make? Reimaa is skeptical. “The OSCE is still there technically, but it no longer has any political significance,” he says with regret. “And as long as Vladimir Putin is in charge in Russia, little positive can come out of a new conference.” If trust is the most important resource in diplomacy, Reimaa is unfortunately right.